Sediments of History

In attempting to temporalise the questions and answers of the Ethiopian student movement I have wanted to pose the question of whether it was possible to open up the present – not by reimagining the future through new longings for ideal-typical social science models, but through alternative conceptions of our inheritance from the past. In order to think through this question, over the past decade I have collaborated with the Ethiopian-Swedish artist Loulou Cherinet to document and theorise the changing landscape of Addis Ababa. As part of this ongoing collaboration, since 2012 Cherinet has repeatedly visited various sites in Addis Ababa in order to periodically photograph the same location from the same vantage point. Under the name Big Data, Cherinet presents the photos of each site as a linear sequence of development that has taken place between 2012 and 2017. Given the rapid changes to the landscape of Addis Ababa, what makes the sequences compelling is that the content of each photo is familiar and yet starkly different as each year passes by. Each sequence examines the sediments of an older modernity (earlier formations of Addis Ababa architecture) that are buried under a new, more up-to-date version of what the ‘modern’ ought to connote.

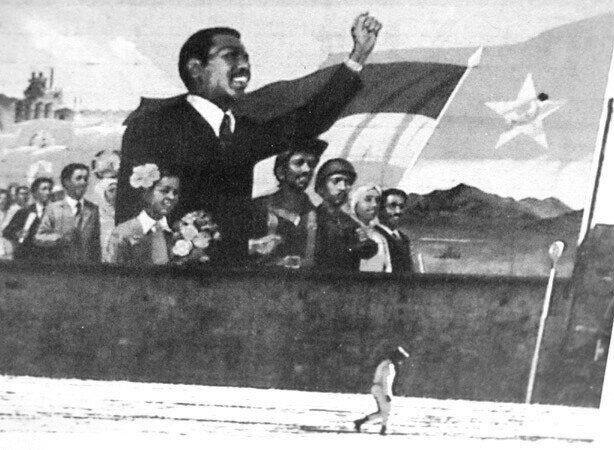

Revolutionary Square - 1970s to present

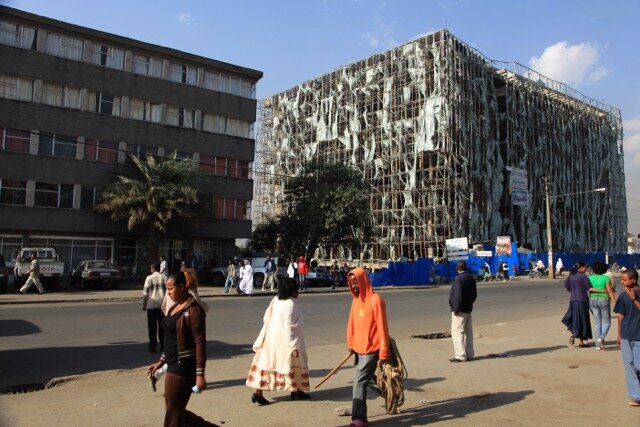

Viewed together, Cherinet’s Big Data documents the landscape of neighbourhoods bulldozed to make way for the coming skyscrapers that already dot the margins of the old neighbourhoods. We see remnants of old houses and old plumbing, as well as people who continue to eke out a living among the rubble left after their houses were expropriated to make way for the newly modern. In some photographs we find a single wall, a remnant of a house torn down, somehow still standing, somehow still providing shelter. The everyday life of the uprooted continues: women still cook and prepare food; herders’ animals linger amidst new condominium-style housing developments, while traditional or old-style building techniques are used to erect structures made of concrete and steel. Most startling, however, are the photos of the abandoned towers. Ghostly testaments: the abandoned towers speak of investors running out of funds, and the already ruined landscape of the new utopian moment that Addis Ababa was supposed to embrace. Overall, in these photos old and new dialogue with each other; the past is no longer silent, and any sense of a seamless transition between past and present is interrupted. Here, one cannot behold new positivist truths discovered by the social sciences; instead the photos seek to reinterpret the present by examining the inheritance of contradictions that have come from the past. Similarly, in this book I have tried to draw attention to the wider attempt to transform social being in Ethiopia as a way to listen to what has been silenced in the very process of social transformation: lives cut short, bodies mangled by social violence. For me, this technique of listening has helped to convey something of the claustrophobia embedded in the social meaning of my case study: the loss of hope for a transformed present. In discussing the story of the protests against the Addis Ababa master plan I have, therefore, wanted to draw parallels to the way in which lack and longing once again confront each other as a social and personal experience in Ethiopia (what I called in Chapter 1 the problematic of Tizita). Any sense of a seamless transition between past and present is interrupted; the body searches for a method towards the redemption of the human bond with nature and other humans. Its method is found in the air that it breathes.

Peri-Urban Addis Ababa 2013-2017

Urban Addis Ababa 2013-2017